By Jasmine C.

“Radical acceptance rests on letting go the illusion of control and a willingness to notice and accept things as they are right now, without judging.” — Marsha Linehan

Radical acceptance – a component of dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT), created by Dr. Marsha Linehan in the 1980s, and a essential tool in my recovery. While DBT has been most widely studied as a treatment for borderline personality disorder, it has also shown promise in the treatment of eating disorders. Interestingly, it emerged from the mind of a woman who spent her adolescence in a psychiatric hospital, and spent much of her early life battling severe mental illness. Regardless of its origin, however, radical acceptance can stand alone as a valuable skill when faced with life’s challenges.

I was first introduced to radical acceptance during a particularly difficult inpatient stay a few years ago. To say that things had gotten bad would be an understatement, and I had more or less given up on the prospect of recovery. I was entirely consumed by the eating disorder. I saw no way out, no life beyond it. My psychiatrist admitted me as an involuntary patient, and so I was forced, internally kicking and screaming, into the hospital.

With my control having been ripped from my unwilling grasp, my initial reaction was to fight to get it back. I refused to comply with the program, I made my distaste for it very clear, and I spent hours plotting my escape. Obviously, this didn’t work. The weeks kept going by, and I was still stuck in the hospital. Meanwhile, I would often hear the nurses and other patients talk about practicing “radical acceptance”, and I gradually came to understand what they meant. Recognizing that some things in life cannot be controlled. Acknowledging that pain is inevitable, but it does pass. Letting go, in the style of Elsa.

Recognizing that some things in life cannot be controlled. Acknowledging that pain is inevitable, but it does pass. Letting go, in the style of Elsa.

Eventually I started to realize that my fighting wasn’t doing anything to change my situation, but was rather making me stressed and miserable, and alienating me from my doctors, nurses, and fellow inpatients. So I decided to try accepting my situation instead. I finished all my meals, went to all the groups, made friends with the other patients, and set my eyes on recovery. It was liberating. A few weeks later, I was made a voluntary patient and was offered the choice of leaving, but I actually chose to stay.

The word “radical” comes from the Latin “radic”, meaning root, and thus radical acceptance refers to a complete, fundamental acceptance of a situation from its root. However, to me it also reflects the other meaning of the word “radical”, the independence of or departure from tradition; innovative or unorthodox. In many ways deciding to stop fighting felt less like “giving up” and more like leaping off a precipice into the unknown and frightening. The freedom it offers is thrilling.

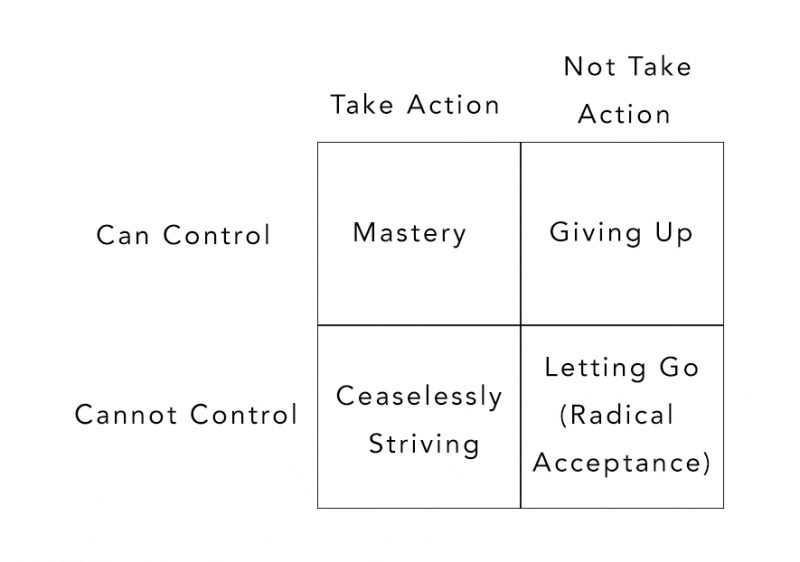

Radical acceptance has also been explained to me in terms of the “personal power grid”:

In a situation you do have control over, taking action can lead to mastery – solving the problem, making things exactly as you want them. In a situation you do not have control over, it will lead instead to “ceaseless striving”, a category I often find myself in. In these situations it is often healthier to not take action, to let go, to accept. Being involuntarily confined to a locked psychiatric unit is an extreme example of a situation in which one does not have control, but this idea applies equally well to many of the painful situations one might encounter.

People with eating disorders are known for our tendency to try and control ourselves and our lives to excess. We have a pathological need to control that often leads to self-destruction. We “ceaselessly strive” to the point of utter exhaustion. And so an integral part of our recovery is learning how to radically accept instead. Rather than judging our bodies as “bad” and trying to change them, the thing to do is accept our bodies as they are. Beyond that, we can use radical acceptance to deal with life’s bigger concerns, the ones we try to cope with by burying ourselves in our eating disorders. It’s easy to get carried away with anxiety, judgments and the racket in your head, but if you take a moment to look at things as they really are, and radically accept that reality, you’ll stumble into an unexpected freedom and peace.

Jasmine is a neuroscience student at the University of British Columbia, and is fascinated by the interaction between mental and physical health. Some of her favourite things include mountains, tea, and her dog, Ollie.