By Kat Bernards

**TRIGGER WARNING: If you live with or are in recovery from an eating disorder, the following post could potentially be triggering**

It’s time for us to talk about To The Bone.

Given the flurry of media attention surrounding the controversial Netflix film, and the complexity of the issues raised by the individuals and organizations who have voiced their opinions of it, Looking Glass has decided to compose a collective response to the film from our perspective as an eating disorder recovery-focused organization. Our response should not be taken as a definitive or prescriptive stance, but rather as a critical lens through which to view both the failures and successes of a Hollywood film that seeks to convey an accurate, intimate portrait of life with an eating disorder. This piece will be triggering to some readers, and it will also discuss spoilers of the film’s plot and ending, so please exercise your best judgment in deciding whether or not to proceed with this article.

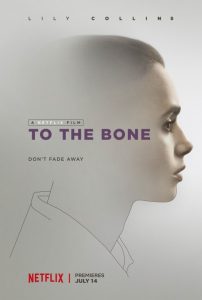

Netflix recently released the film, written and directed by Marti Noxon, which partly tells the story of Noxon’s own experience with an eating disorder. Starring Lily Collins, who is herself an eating disorder survivor, To The Bone follows one woman’s struggle and her experience at an inpatient treatment centre. It’s important to remember that the movie is just that – a movie. It’s a partial fiction, not an exposé of every eating disorder sufferer’s history, and is ultimately intended as entertainment.

While it can easily be seen as a triumph that we actually have a Hollywood film that shines a light on the darkness of eating disorders, To The Bone’s focus on physical appearance, disordered behaviours, and the burgeoning romance between the two main characters all serve to delegitimize the real work that goes into real-life recovery. Ultimately, the film is one long missed opportunity for a more in-depth exploration of its themes, and it also – inadvertently or not – reinforces some of the harmful stereotypes that have long been associated with eating disorders and mental health.

Eating disorders and thinness are fetishized throughout the film, and these are even further emphasized by the decisions and processes involved in the film’s production. It’s no secret that Lily Collins made herself extremely thin to take on this role, and we question whether this was necessary for the part. While we understand that actors often go to extremes to fully prepare for the roles they play, we as a society ought to be well past the point of shrugging our shoulders and accepting that this is the cost of doing business in Hollywood. It’s time to recognize that it’s one thing to create a beautiful, spunky, sexual, resilient female lead, but to suggest that her charm is entirely derived from the very disorder that is killing her is at best misguided, and at worst, incredibly dangerous.

Ultimately, the film is one long missed opportunity for a more in-depth exploration of its themes, and it also – inadvertently or not – reinforces some of the harmful stereotypes that have long been associated with eating disorders and mental health.

It’s dangerous because Collins’ character, Ellen, is in pain. And yet her pain is constantly devalued by the lighthearted depiction of her eating disorder behaviours – as well as those of all the other residents at Dr. Beckham’s treatment centre. For those of us who have personally known an eating disorder, we may see flickers of our own or a loved one’s experience in these characters’ comments and behaviours – especially, perhaps, in the way the film addresses the disordered “voice” that so often comes with the territory, or the ways in which loved ones can make mistakes even as they try their best to be supportive – and we may even find comfort in a moment of dark humour, if we are in a stable enough place to not be triggered by it. But we may also struggle to see ourselves at all in this film – eating disorders are not, after all, a one-size-fits all phenomenon dominated by stereotypically ‘skinny white women.’ And for those who view this film with no prior understanding of eating disorders, or who may be relying on such stereotypes for information, the stories on display offer little insight into the harsh reality of the disorder. The pain of the sufferers is too often minimized by the one-dimensional, unsympathetic portrayal of their disorders.

The upshot of this is that we don’t see an eating disorder’s intrusiveness, its control, or its cruelty played out in what these people are experiencing in their daily struggle to recover: instead, Ellen laughs hysterically while spitting out her food on a date; Megan’s loss of her child is played off as selfish; Tracey comes across as cold and judgmental of the other residents’ behaviours; Anna’s constant cheating on the program makes her seem shallow and competitive rather than being controlled by a sickness; and Kendra appears to be the film’s tokenized solution to Hollywood’s lack of diversity – a contrived, 3-for-1 nod to the Black, queer, and plus-sized communities. Meanwhile, Pearl’s fear of adulthood does have the heartbreaking ring of authenticity, but it’s unfortunately used only to juxtapose the scripted wit and wisdom that is reserved explicitly for Ellen and Luke. Their budding romance takes up so much space in the film that there is no room to develop the other characters, or to adequately explore the full and painful experience of their unique eating disorders – instead, they are trivialized and played for cheap laughs.

The pain of the sufferers is too often minimized by the one-dimensional, unsympathetic portrayal of their disorders.

Which brings us to Luke. It’s refreshing to see a male eating disorder sufferer portrayed in the film, but his character is deeply problematic in several ways. He hyper-sexualizes Ellen as well as her disorder, and his constant cheerleading of the others’ recovery is at odds with his obsession over Ellen and her physical appearance. We cannot pretend that he is a deeply-feeling romantic who sees only her soul – he sees her sickness, and he devours it. As the resident who is the most advanced in recovery, he also plays into the traditional Hollywood trope of a male rescuer –alongside Keanu Reeves’ Dr. Beckham – by cheering on the others and role-modeling (aka: mansplaining) for them what recovery should look like.

In contrast to Luke, the other patients appear weak and histrionic, needing his constant reassurance that they still have value. We are given false hope that Ellen will move past this untimely romance when she rejects Luke and his insistence that she must be his “next thing” – only to have her inexplicably return to him in a vision at the end of the film, in which he is not only her rescuer, but her recovery champion. Perhaps worst of all, Luke is the only character who is given a tangible, non-psychological excuse for having an eating disorder in the first place: his dance career has been destroyed by a knee injury, which led to his spiraling into anorexia. The problem is that eating disorders are inherently psychological, and to suggest that men’s eating disorders are less so is feeding directly into the shame and stigma that prevents so many sufferers from seeking help.

To The Bone does have something very legitimate to offer: a starting point for a more serious, in-depth discussion around eating disorders. As a Hollywood movie, it cannot be expected to represent all of our stories and lived experiences, nor can it be expected to properly educate the public about eating disorders. It leaves questions unanswered, and sentences unfinished. But for all its missteps, it does create space for others to come forward and do better – and we must hold space for that to continue to happen.

Kat graduated from Simon Fraser University with a degree in Psychology, and is thrilled to have joined the Looking Glass Foundation staff. She loves live music, theatre, writing, and singing when no one is listening.